Article

The Speech Accessibility Project is helping researchers and companies improve speech recognition technology by sharing annotated recordings of people who have disabilities that affect their voices.

That’s not the only way it’s making a difference, though. The project recently hosted a recent competition that shared recordings with researchers from all over the world, who showed unprecedented improvements in technology that recognizes speech that’s not typical. Twenty-two teams from around the world participated.

“The results were amazing,” said Mark Hasegawa-Johnson, a professor of electrical and compute reengineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and leader of the project.

Competitors focused on two key metrics of speech recognition technology: word error rate, a common metric used to measure the accuracy of speech-to-text systems, and semantic score, which considers the actual meaning of the speech and text

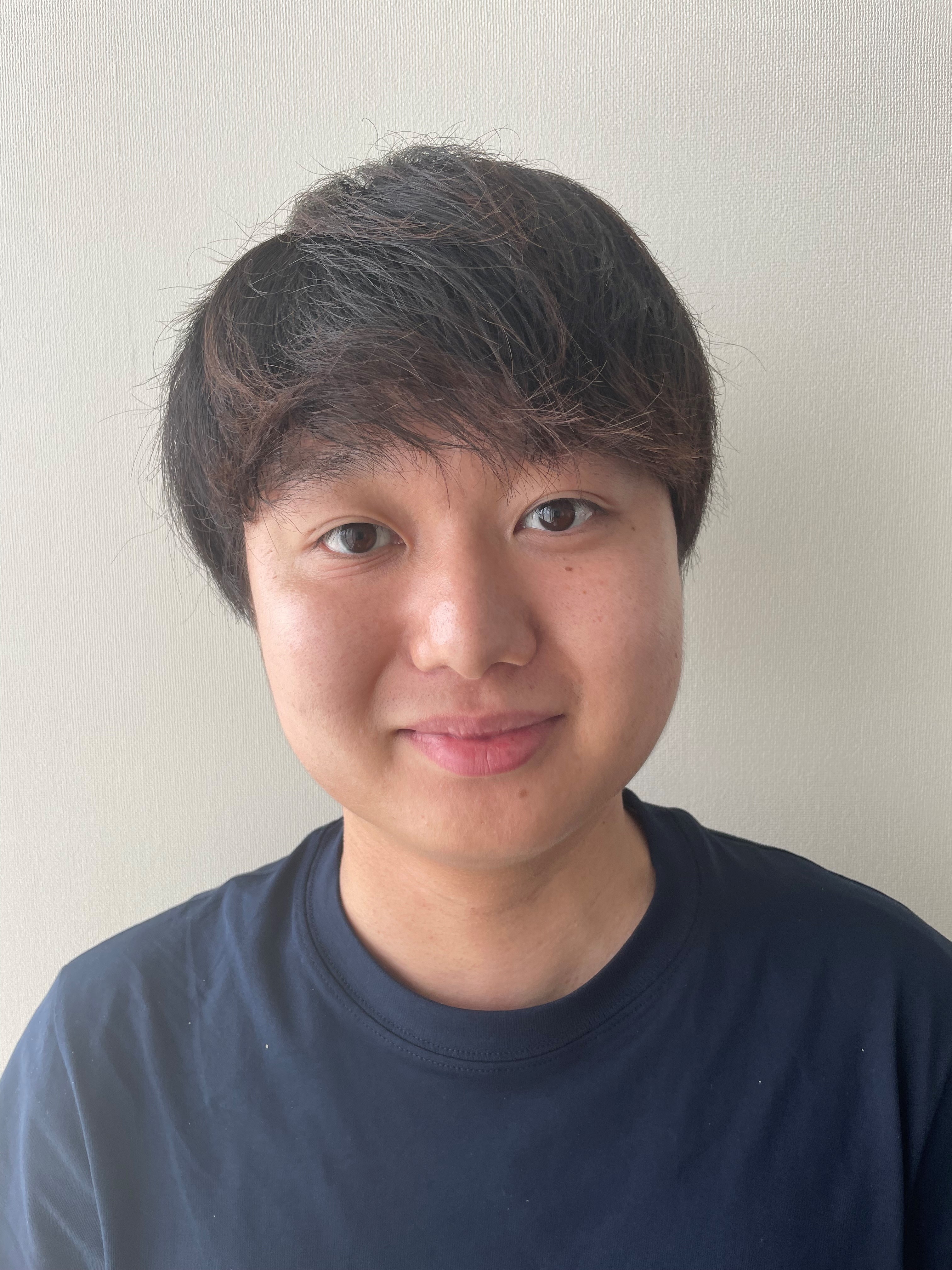

A team of researchers from Toyohashi University of Technology in Aichi Prefecture, Japan, won both parts. They focused specifically on the word error rate, said Kaito Takahashi, the leader of Team SLP-Lab, because they knew it had a strong correlation with the semantic score.

The team’s word error rate on one test was about 6% and 8% on another. Current open source speech recognition technology tools have a word error rate of about 15% and 18% on the same tests.

“So far, we've only tested a simple approach,” Takahashi said. “Moving forward, we plan to explore more advanced techniques to further improve recognition accuracy,”

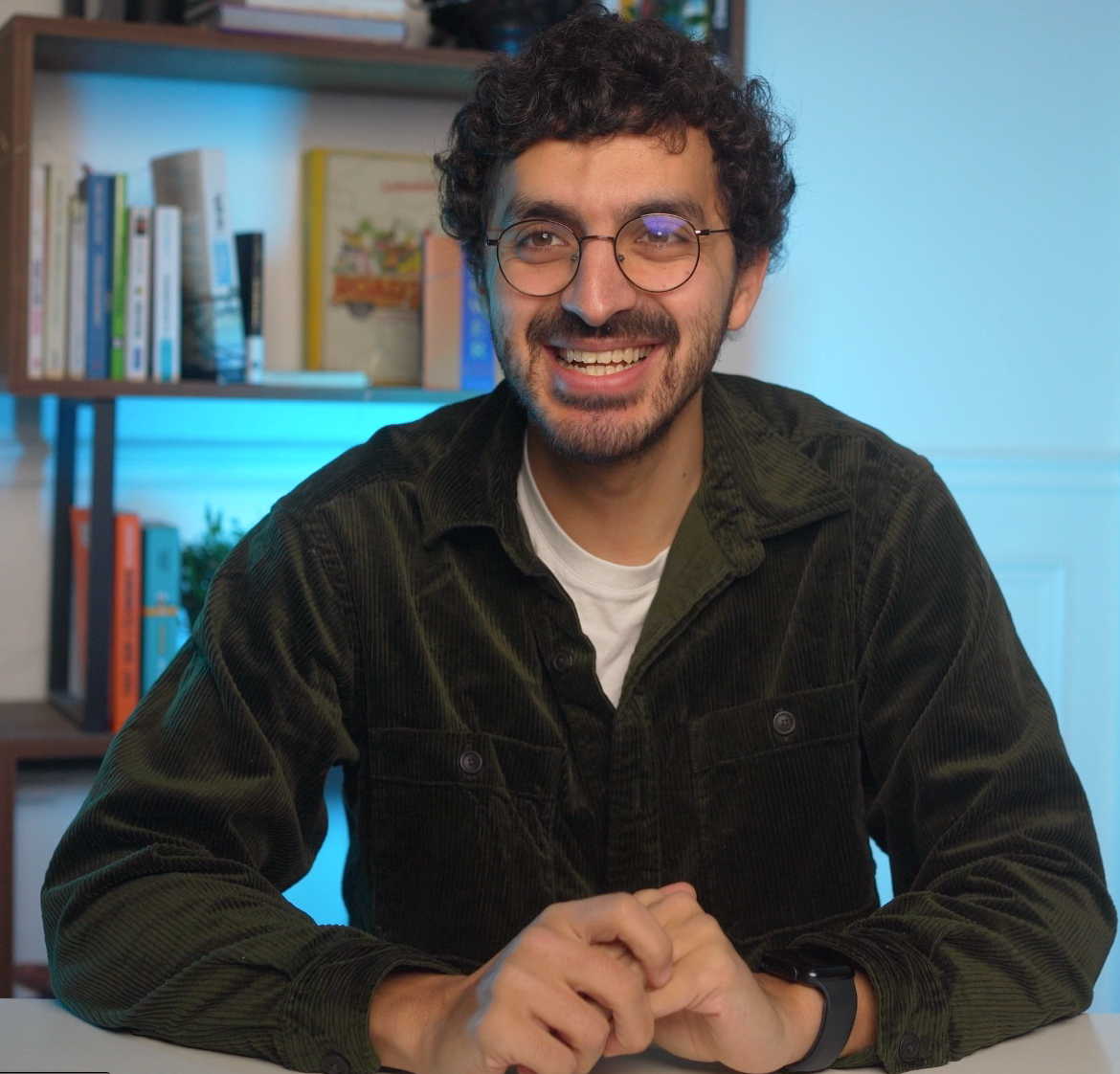

Rachid Riad, co-founder and chief technology and science officer of Callyope, also competed in the challenge. Callyope is a France-based company developing audio-language models that monitor mental health and cognitive symptoms across central nervous system conditions by analyzing patients’ speech patterns.

“The Speech Accessibility Project challenge is truly remarkable in its scope and scale,” Riad said. “This dataset enabled us to demonstrate that our model merging approach can transcribe speech for individuals with brain disorders with significantly greater accuracy than existing open-source solutions.”

Riad and his team discovered that the project’s diverse dataset also improved recognition performance on internal datasets across multiple languages and various conditions.

“Traditional transcription systems like Whisper struggle when patients experience speech disturbances such as dysarthria or apraxia,” Riad said. “The results of this challenge pave the way for better accessibility of voice AI technologies that were previously inaccessible to patients. These advances also enabled Callyope’s foundation model to leverage more precise transcriptions when conducting symptom assessments.”

Xiuwen Zheng, a graduate student working with Hasegawa-Johnson, set up the competition and worked through technical challenges like making sure competition’s test data (used to evaluate the submissions) remained private.

“It's inspiring to see different groups approaching the challenge from various angles using innovative strategies,” Zheng said. “We're pushing the boundaries of speech recognition for individuals with speech disorders, which is satisfying because I know we together are making valuable contributions.”

Zheng and Hasegawa-Johnson are co-authoring a paper documenting the competition for Interspeech 2025, an annual conference focused on the science and technology of spoken language processing. Many competitors are expected to submit papers on the topic, as well.

Speech Accessibility Project

405 N Mathews Ave., Urbana, IL 61801